-40%

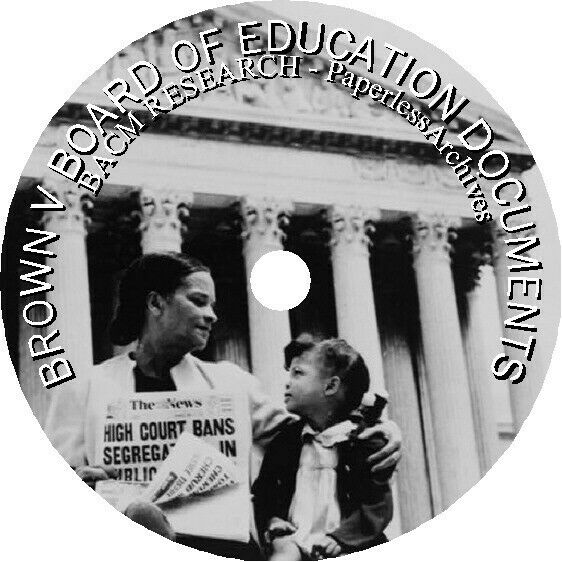

Brown v. Board of Education Case Documents

$ 5.81

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

Brown v. Board of Education Case DocumentsBrown et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas Case Documents

729 pages of documents related to the Brown v. Board of Education Topeka, Kansas case, archived on CD-ROM.

In the 1930's the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) pursued lawsuits that sought to force admission of blacks into universities at the graduate level, where establishing separate but equal facilities would be difficult and expensive for the states. At the forefront of this movement was Thurgood Marshall, a young black lawyer who, in 1938, became general counsel for the NAACP's Legal Defense and Education Fund. Their significant victories at this level included Gaines v. University of Missouri in 1938, Sipuel v. Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma in 1948, and Sweatt v. Painter in 1950. In each of these cases, the goal of the NAACP defense team was to attack the "equal" standard so that the "separate" standard would in turn become susceptible.

In 1950, members of the Topeka, Kansas, Chapter of the NAACP challenged the "separate but equal" doctrine governing public education, through a class action suit when they were denied the opportunity to enroll their children in the white only schools. The case came to be known as Brown v. Board of Education. Although in this case and four similar cases: Harry Briggs, Jr., et al. v. R.W. Elliott, et al.; Dorothy E. Davis et al. v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, et al.; Spottswood Thomas Bolling et al. v. C. Melvin Sharpe et al.; and Francis B. Gebhart et al. v. Ethel Louise Belton et al, it acknowledged some of the plantiffs' claims, a three-judge panel at the U.S. District Court that heard the cases ruled in favor of the school boards. The lower courts cited the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling of the United States Supreme Court as precedent.

Homer Plessy, a black man from Louisiana, challenged the constitutionality of segregated railroad coaches, first in the state courts and then in the U.S. Supreme Court. The high court upheld the lower courts, noting that since the separate cars provided equal services, the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment was not violated. Thus, the "separate but equal" doctrine became the constitutional basis for segregation. One dissenter on the Court, Justice John Marshall Harlan, declared the Constitution "color blind" and accurately predicted that this decision would become as baneful as the infamous Dred Scott decision of 1857.

The plantiffs then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

When the cases came before the Supreme Court in 1952, the Court consolidated all five cases under the name of Brown v. Board of Education. This grouping was significant because it represented school segregation as a national issue, not just a southern one. Thurgood Marshall personally argued the case before the Supreme Court. Although he raised a variety of legal issues on appeal, the most common one was that separate school systems for blacks and whites were inherently unequal, and thus, violate the "equal protection clause" of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Furthermore, relying on sociological tests, such as the one performed by social scientist Kenneth Clark, and other data, he also argued that segregated school systems had a tendency to make black children feel inferior to white children, and thus, such a system should not be legally permissible. The lawyers for the school boards based their defense primarily on precedent, such as the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling, as well as on the importance of states' rights in matters relating to education.

Meeting to decide the case, the Justices of the Supreme Court realized that they were deeply divided over the issues raised. While most wanted to reverse the Plessy V. Ferguson decision and to declare segregation in public schools to be unconstitutional, they had various reasons for doing so. Unable to come to a solution by June 1953, the end of the Court's 1952-1953 term, the Court decided to rehear the case in December 1953. During the intervening months, however, Chief Justice Fred Vinson died and was replaced by Governor Earl Warren of California. President Eisenhower believed Warren would follow a moderate course of action toward desegregation. His feelings regarding the appointment are detailed in the closing paragraphs of an October 23, 1954 letter from President Dwight D. Eisenhower to E. E. "Swede" Hazlett, which is a part of this document collection.

After the case was reheard in 1953, Chief Justice Warren was able to do something that his predecessor had not, bring all of the Justices to agree to support a unanimous decision declaring segregation in public schools unconstitutional. On May 14, 1954, he delivered the opinion of the Court, stating that "We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. . ."

Expecting opposition to its ruling, especially in the southern states, the Supreme Court did not immediately try to give direction for the implementation of its ruling. Rather, it asked the attorney generals of all states with laws permitting segregation in their public schools to submit plans for how to proceed with desegregation. After still more hearings before the Court concerning the matter of desegregation, on May 31, 1955, the Justices handed down a plan for how it was to proceed; desegregation was to proceed with "all deliberate speed." Although it would be many years before all segregated school systems were to be desegregated, Brown and Brown II, as the Court's plan for how to desegregate schools came to be called, were responsible for getting the process underway.

Documents on the Disc:

Brown et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka Key Documents.

86 pages of key documents concerning the Brown V. Board of Education case.

Documents date from 1951 to 1957. Documents include: Complaint against Board of Education of Topeka. Court order, Oliver Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. Dissenting Opinion of Judge Waites Waring in Harry Briggs, Jr., et al. v. R. W. Elliott, Chairman, et al. Order for Appearance of Thurgood Marshall. Memorandum, Dwight D. Eisenhower to Secretary of Defense regarding Segregation in Schools on Army Posts. Letter from Texas Governor Allan Shivers to Dwight D. Eisenhower regarding school segregation. Letter from Dwight D. Eisenhower to South Carolina Governor James Byrnes stating his views on school segregation. Letter from Louisiana Governor Robert Kennon to Dwight D. Eisenhower. Letter from South Carolina Governor James Byrnes to Dwight D. Eisenhower. Letter from Dwight D. Eisenhower to Louisiana Governor Robert Kennon. Earl Warren's draft memo on the Brown case. Earl Warren's handwritten notes on the opinion for the decision in Brown et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka. Associate Justice William O. Douglas' handwritten note on Warren's handling of the case. Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter's handwritten note to Earl Warren. Associate Justice Harold H. Burton handwritten note to Chief Justice Earl Warren. Felix Frankfurter's Draft Decree in Brown II. Earl Warren's handwritten notes for the final decree.

Integration of Dallas Public Schools FBI Files

527 pages of FBI files covering the integration of Dallas public schools.

The Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, did not instantly solve the problem of school segregation. A prime example was the status of the Dallas public school system in the 1950's and early 1960's.

In a 1955 case seeking to desegregate the Dallas public school system, U.S. District Court Judge William S. Atwell ruled against the plaintiff. Judge Atwell claimed the Supreme Court in the Brown decision overstepped its authority. The NAACP brought suit against the Dallas school system in the case of Bell v. Rippy. In this case Atwell also ruled against the plaintiffs in 1957, claiming the Supreme Court over stepped its power in the Brown case. In both cases, Atewell was overruled by the Fifth Circuit of Appeals. Judge Atwell crafted a plan that would desegregate Dallas public schools over approximately a twelve year period. The Fifth Circuit also struck down Atwell's desegregation plan. In 1960, Dallas was the largest city in the Southern United States to have a segregated school system. Under order of the Fifth Circuit, Dallas began desegregating its schools in the fall of 1961.

The files date from 1956 to 1962. Most of the early tracking of the cases in the files are from photocopied newspaper articles. When complaints were made to the FBI by Thurgood Marshall, that Texas law enforcement tried to intimidate plaintiffs in the Bell v. Rippy case, a segregation lawsuit against the Dallas public schools, the FBI became more involved. The files chronicle some civil unrest that occurred as Dallas inched its way toward desegregation of its public school system

Mendez et al. v. Westminster School District of Orange County Documents

116 pages of documents dealing with the Mendez et al. v. Westminster School District of Orange County case. This early school desegregation case preceded Brown v. The Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. Some see this case as a state level model for Brown V. Board of Education. Amicus curiae briefs were filed in this case by the NAACP, coauthored by Thurgood Marshall.

In the Fall of 1944, Gonzalo and Felicita Mendez tried to enroll their children in the Main Street School, which Gonzola had attended as a child. However, the school district had redrawn boundary lines that excluded the Mexican and Latino neighborhoods. The school district also segregated Japanese American children. However, it passed a resolution in January 1945 allowing these children to attend the Main Street School. The Mendez children were assigned to Hoover Elementary School, which was established for Latino children. Other Orange County Latino parents faced similar situations with their children.

With the help of the United Latin American Citizens (LUCAC), they joined with the Mendez family and sued four local school districts, including Westminster and Santa Ana, for segregating their children and 5,000 others. The plaintiffs charged, "That all children or persons of Mexican or Latin descent ... are now excluded from attending, using, enjoying and receiving the benefits of the education, health and recreation facilities of certain Schools." And "that said children are now and have been segregated and required to and must attend and use certain Schools in said District and Systems, reserved for...children and persons of Mexican and Latin descent..."

This suit was heard in both state and federal courts. At the state trial, Orange County superintendents used stereotypical imagery of Latinos to explain the basis of school policy. One declared, "Mexicans are inferior in personal hygiene, ability, and in their economic outlook." He further stated that their lack of English prevented them from learning Mother Goose rhymes and that they had hygiene deficiencies, like lice, impetigo, tuberculosis, and generally dirty hands, neck, face and ears. These he stated warranted separation.

The attorney for Mendez, David Marcus, called in expert social scientists as witnesses to address the stereotypes. He also challenged, based on the 14th Amendment, the constitutionality of education segregation. He also had Fourteen-year-old Carol Torres take the stand to counter claims that Mexican children did not speak English. Felicita Mendez also gave testimony about her family life: "We always tell our children they are Americans." It took also almost a year for state Judge Paul McCormick to make his decision. He ruled that there was no justification in the laws of California to segregate Mexican children and that doing so was a "clear denial of the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment". The school districts filed an appeal, partly on the basis of a states' rights strategy. In 1947 the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court upheld the state court's ruling and the Orange County school districts dropped the case.

The case resulted in the California legislature passing the Anderson bill, a measure that repealed all California school codes mandating segregation. The bill was then signed by the Governor Earl Warren, who years latter as the Chief Justice authored the opinion in Brown V. Board of Education.

Documents date from 1945 to 1946. Documents include:

Petition from Mendez et al. v. Westminster School District of Orange County: This petition summarizes the complaint made by several parents of children in the Westminster, Garden Grove, and El Modeno School Districts and the City of Santa Ana schools. It charges that the schools were violating students' civil rights by segregating students of "Mexican and Latin" ancestry in separate schools. Answer of Westminster School District of Orange County, et al. From Mendez et al. v. Westminster School District of Orange County. Petitioners' Opening Brief: This brief presents the petitioners' detailed legal arguments against the use of segregation by several Orange County, CA, school districts. Conclusions of the Court: This document sets forth the finding of Judge Paul J. McCormick, which was in favor of the petitioners. Judgment and Injunction: In this judgment, Judge Paul J. McCormick barred the school district from segregating students on the basis of race.

The disc contains a text transcript of all recognizable text embedded into the graphic image of each page of each document, creating a searchable finding aid.

Text searches can be done across all files on the disc.

CD-ROM works with Windows or MAC